- Home

- Miles J. Unger

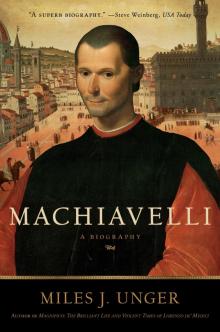

Machiavelli

Machiavelli Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

Select Cast of Characters

Maps

Prologue: The Malice of Fate

I Born in Poverty

II A Sword Unsheathed

III The Civil Servant

IV Sir Nihil

V Exit the Dragon

VI Men of Low and Poor Station

VII The Stars Align

VIII Reversal of Fortune

IX Dismissed, Deprived, and Totally Removed

X The Prince

XI Vita Contemplativa

XII The Sage of the Garden

XIII Nightmare and Dream

XIV Finger of Satan

Photographs

About Miles J. Unger

Notes

Bibliography

Index

To Dad and Debi, with love and admiration

SELECT CAST OF CHARACTERS

Cesare Borgia, Duke Valentino (c. 1475–1507)

Rodrigo Borgia, Pope Alexander VI (b. 1431, Pope 1492–1503)

Biagio Buonaccorsi, friend and correspondent of Machiavelli

Charles V, Hapsburg Holy Roman Emperor (1500–58)

Charles VIII, King of France (1470–98)

Francesco Guicciardini, Machiavelli’s friend and correspondent, historian, governor of the Romagna (1483–1540)

Louis XII, King of France (1462–1515)

Bernardo Machiavelli, father of Niccolò (c. 1425–1500)

Niccolò di Bernardo Machiavelli, Second Chancellor of Florence, political theorist, playwright (1469–1527)

Marietta Corsini, wife of Niccolò Machiavelli

Children: Primavera, Bernardo, Lodovico, Guido, Bartolomea, Piero

Maximillian I, Hapsburg Holy Roman Emperor (1459–1519)

Giulio de’ Medici, Pope Clement VII (b. 1478, Pope 1523–34)

Lorenzo de’ Medici, Il Magnifico (“The Magnificent”) (1449–92)

Sons of Lorenzo the Magnificent:

Piero de’ Medici (“The Unfortunate”) (1472–1503)

Giovanni de’ Medici, Pope Leo X (b. 1475, Pope 1513–21)

Giuliano de’ Medici, Duke of Nemours (1479–1516)

Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino (1492–1519)

Giuliano della Rovere, Pope Julius II (b. 1443, Pope 1503–13)

Girolamo Savonarola, Prior of San Marco, prophet (1452–98)

Ludovico Sforza, Il Moro (“The Moor”), Duke of Milan (1452–1508)

Piero Soderini, Gonfaloniere of Florence (1450–1522, Gonfaloniere 1502–12)

Giovanni Vernacci, nephew of Niccolò Machiavelli

Francesco Vettori, Machiavelli’s correspondent, Florentine ambassador to Pope Leo X (1474–1539)

PROLOGUE

THE MALICE OF FATE

“I have written down what I have learned from these conversations and composed a little pamphlet, De principatibus, in which I delve as deeply as I can into the subject, asking: What is a principality? How many kinds are there? How may they be maintained and why are they lost?”

—NICCOLÒ MACHIAVELLI, LETTER TO FRANCESCO VETTORI, DECEMBER 10, 1513

IT HAD BEEN A BAD YEAR FOR NICCOLÒ MACHIAVELLI. Not only had he lost his job—“dismissed, deprived and totally removed,” read the decree that singled out the Second Chancellor of Florence with vindictive thoroughness—but the republic he had served faithfully for the past fourteen years had fallen beneath the tyrant’s boot. His friends fled as foreign armies descended upon the city, replaced by people with little reason to wish him well. To those who had followed Machiavelli’s career and recalled his abrasive manner, his current isolation came as no surprise. Often during the years he had served in government he had spoken a little too bluntly or pushed his agenda with more enthusiasm than tact, and now that he was in need of allies in high places they proved to be in short supply.

These repeated blows were all the more painful since it was hard to deny the fact—and, were he inclined to forget it, his many detractors were only too happy to remind him—that Machiavelli’s policies were largely responsible for the disaster. The citizen militia that had been his proudest creation had disgracefully turned tail at the first contact with the enemy, abandoning the neighboring city of Prato to be sacked and pillaged, dooming the independent Florentine Republic.

Worse was to come. With his friends disgraced and his enemies triumphant, Machiavelli’s name appeared on a list compiled by a man captured while plotting to overthrow the new regime. On February 18, 1513, Machiavelli was arrested and thrown into prison. Dragged periodically from his dank, vermin-infested cell in Le Stinche, only a few short blocks from his old office, he was tortured with repeated drops of “the rope” in an attempt to extract a confession of guilt. It was an ordeal that might have broken a less resourceful man, but Machiavelli, making the best of a grim situation, chose to regard it as something of a character-building exercise. Only a few weeks later, still recuperating from his injuries, he wrote to his friend Francesco Vettori: “And as for turning my face toward fortune, you should take at least this pleasure from these troubles of mine, that I bore them with such stoicism that I am proud and esteem myself more highly than before.”

His dignity, in fact, was about all he had salvaged from the disaster of the past months. Machiavelli’s state of mind can be gauged by a sonnet he composed during his prison stay. The honesty and grim humor are typical, as is his capacity to laugh at himself:

I have, Giuliano,i on my legs a set of fetters,

with six pulls of the cord on my shoulders;ii my other miseries

I do not intend to recount to you, since so the poets are treated!

These broken walls generate lice so swollen that they look like

flies; never was there such a stench . . . .

As in my so dainty hospice.

Rather than wallowing in self-pity, Machiavelli was inclined to meet his reversal with a wisecrack and a shrug. The image of his “dainty hospice” crawling with lice who fatten themselves on the wasting flesh of prisoners is half farce, half tragedy—a play of light and shadow that runs through both his political and literary works. “So the poets treated are treated!” he snorts, making light of his predicament and, with more than a hint of self-mockery, placing himself among the long line of artists who have suffered for their craft. One of the clearest signs that his spirit remained strong was that he found the time to take a swipe at one of his favorite targets, the pious fools whose answer to life’s every problem was prayer:

What gave me most torment was that, sleeping near dawn, I

Heard them chanting the words: “We are praying for you.”

Now let them go away, I beg, if only your pity may turn itself

Toward me, good father, and loosen these cruel bonds.

Who but Machiavelli would insist that having to listen to prayers all night was more painful than a session with the state torturer? He would have been mortified if in a moment of weakness he suddenly embraced religious beliefs he had scoffed at most of his adult life. He was not one of those fair-weather skeptics who deny God in the good times only to rediscover Him in their hour of need. He refused to accept the easy comfort of religious pabulum, preferring to take his chances with fickle Fortuna rather than place an existential bet with the priests he regarded as little more than charlatans and swindlers.

In any case, it was not the power of prayer that freed him after a three-week sojourn in his “dainty hospice,�

�� or even the charm of his jocular little poem, but his captors’ grudging admission that they lacked any real evidence he was involved in the plot.iii But his release was not the end of his difficulties. Even after he was freed Machiavelli remained under a cloud of suspicion. He was barred from government service, the only career he had ever known and the only one in which he could employ his distinctive talents. Short of losing his life—something that seemed more than likely at one point—it his hard to see how the past twelve months could have brought more disappointment and sorrow.

These days he rarely made the journey to Florence, a few hours’ ride by mule or on foot along the winding road that led through the olive groves and vineyards of the Tuscan countryside. The handful of friends who had remained loyal to him during his recent troubles could now find him living in obscurity at his farm in the village of Sant’ Andrea in Percussina, trying, without much success and even less enthusiasm, to eke out a meager living from his modest patrimony. From his fields he could see the red-tiled rooftops of his beloved Florence, crowned by the soaring arc of Brunelleschi’s dome and the angular tower of the Palazzo della Signoria, the government building that had been his place of work in recent years.iv But far from providing solace, the view was a constant reminder of a life in shambles. The depth of his anguish can be felt in a note he scribbled in the margins of a document he was working on: “post res perditas,” it read, “after everything was lost.”

One consolation was that without a real job he had plenty of time on his hands to philosophize, to put his troubles behind him, and to try to draw larger lessons from his own experience. As he wandered beneath the bright Tuscan sky and gazed at the city shimmering in the distance, he gained new perspective on the human condition. On occasion he gave vent to his bitterness, but even when his mood darkened he tried to see the bigger picture. In a poem titled “On Ingratitude or Envy” he contemplated the dismal fate of those who served their country well, only to find themselves repaid with slander:

Hence often you labor in serving and then for your good service

receive in return a wretched life and a violent death.

So then, Ingratitude not being dead, let everyone flee from courts

and governments, for there is no road that takes a man faster to

weeping over what he longed for, when once he has gained it.

However sound this last piece of advice, Machiavelli himself was incapable of adopting it. Like someone who keeps returning to an abusive relationship, he would no doubt have leapt at a chance to exchange his current indolence for the government halls from which he had been banished.

To his friend Francesco Vettori, who was complaining about the minor inconveniences of life in Rome, where he was serving as Florentine ambassador to the Holy See, Machiavelli replied with a touch of sarcasm: “I can tell you nothing else in this letter except what my life is like, and if you believe it is worth the exchange, I would be happy to swap it for yours.”

Few people were as ill suited to the quiet life of the countryside as Machiavelli. He was a man of the city who thrived on sociability and the stimulation that came from lively conversation. A keen observer and unsparing chronicler of the human animal, here among the beasts of the field he found little to excite his imagination. He did what he could to maintain his mental agility, but the company he now kept was a far cry from the cardinals and dukes with whom he was used to spending his time. “I wander over to the road by the inn,” he reported, “and chat with the passersby, asking them news of their countries and various other things, all the while noting the varied tastes and fancies of men.” In other words he trained on the local rustics those same sharp eyes that were once so quick to size up the ambition of a king or discover the inscrutable designs hidden in a bland ambassadorial dispatch. There is the same insatiable curiosity, the same need to examine the smallest incident or quirk of character for insights that might hint at universal laws. But there was no denying that his singular talents were wasted as he puttered about his small property, tending to the petty chores that seemed to puzzle him more than the intricacies of an international treaty.

Perhaps out of frustration, or merely to relieve the boredom of his existence in Sant’ Andrea, he engaged in petty quarrels with his neighbors and then described them in letters to friends. They would have gotten the joke immediately. A few months ago he was dining with kings; now he was reduced to butting heads with peasants. “Having eaten,” he wrote to Vettori,

I return to the inn where I usually find the innkeeper, a butcher, a miller, and a couple of kiln workers. With them I waste the rest of the day playing cricca [cards] and backgammon, games that spark a thousand squabbles and angry words, and though for the most part we are arguing over only a penny or two, you can hear us yelling all the way to San Casciano. Thus, cooped up among these lice, I get the mold out of my brain and lash out at the malice of my fate, content to be trampled upon in this manner, if only to see whether fortune is ashamed to treat me so.

But even as he slummed with the locals he began to plot a return to public life. While fate (Fortuna, as he often calls her) had treated him shabbily, Machiavelli had not given up hope of returning to active duty. He would wrestle this capricious goddess to the ground and wring what he could from her, “for,” as he was soon to write with more pugnaciousness than gallantry, “fortune is a woman and in order to be mastered she must be jogged and beaten.”

And so in the winter of 1513 he conceived a plan to ingratiate himself with those who now called the shots in Florence—the Medici and their henchmen, whose return to the city had marked the beginning of all his troubles. To some of his former colleagues, his eagerness to beg a job from the same people who had toppled the democratically elected government was inexcusable, and Machiavelli’s apparent about-face has continued to earn him the scorn of generations of critics. At best it seems like rank hypocrisy, at worst the sign of a man willing to betray every principle to further his career. But neither charge is fair. It is true that Machiavelli had been an ardent supporter of Florentine democracy. He had toiled on behalf of its elected government for fourteen years, at great cost to both his health and his pocketbook. He had stood by his feckless and ungrateful colleagues when less conscientious men had shirked their duty or profited at the public’s expense, and instead of enriching himself with bribes that fell so easily into the pockets of those who worked in government service, he left office no better off than he had entered it. As he himself noted, “my loyalty and honesty are proven by my poverty.”

The truth was that no matter how much he favored Florence’s republican institutions, his patriotism was something far more visceral. His love of country was an intense and irrational passion. This was a rare weakness in a man who famously spurned conventional piety and excelled at exposing human foibles. Few were more adept at tripping up a religious believer in the tangle of his own contradictions, or took more delight in ridiculing the amorous gymnastics of an older colleague mooning over a young beauty. Friends forgave the barbs launched by the man they dubbed Il Machia (the spot or the stain) not only because he usually delivered them with disarming humor, but also because he was happy to offer up his own delinquencies to the ridicule of others. But when it came to the fierce loyalty he felt toward his native land, he would neither examine nor question it. “I love my city more than my own soul,” he once confessed (a statement that perhaps says as much about his disregard for his immortal soul as it does about his patriotism) and it is this nationalist fervor that is the guiding passion of his life, the one fixed point toward which all his thought and action pointed.v It explains all the apparent inconsistencies in his politics and absolves him of the charges of hypocrisy that have dogged him for almost five hundred years. Now that the country he loved was the property of the restored Medici dynasty, he was determined to swallow his pride, if not his principles, and make his peace with those who ruled the state.

This would be no easy task. True, all charges against him h

ad been dropped, but the authorities, slightly paranoid like all new regimes of questionable legitimacy, continued to snoop around, looking for any piece of incriminating evidence that might put the troublesome former Second Chancellor away for good. Machiavelli’s rehabilitation would have been a simpler task had either his pedigree or his bank account been more impressive, but lacking the means to bribe his way back into the good graces of the current rulers, he would have to fall back on his native ability, offering his potential masters the only gift he had: the insights he had acquired in a decade and a half of loyal service to the state. As he sat down to compose his masterpiece, the brief work that would ensure his place in history, he had rather limited goals in mind. Indeed, had he been a better businessman it is unlikely he would ever have turned to writing and his name would have been quickly forgotten, a fact he himself seemed to recognize: “fortune has arranged it that because I can speak neither of the silk trade nor the manufacture of woolen cloth, nor of profits or loss, I must speak of matters of state.”

It in no way diminishes Machiavelli’s achievement to point out that his greatest work was written with prosaic goals in mind; often it is the specter of the wolf at the door that stimulates an artist’s best work. Without his civil service salary Machiavelli had difficulty providing for his family, a needy brood that now included a wife and five young children. “I am wasting away,” he complained, “and cannot go on like this much longer without becoming so reduced by poverty. And as always, I desire that these Medici princes would put me to work, even if that means beginning by rolling a stone.”

So it was that he set about distilling all he had learned in a single slender volume—“this little whimsy of mine,” he called it dismissively—which he intended to dedicate to Giuliano de’ Medici, brother of the current Pope and a man whose friendship he had to cultivate were he to have any hope of prospering in Medicean Florence.vi Machiavelli himself sketched the scene as he sat down to write his most famous work. The charming picture he conjures of the scholar at his desk, putting aside his worries to commune with the ancients, is curiously at odds with the sinister reputation of the book and of the man who wrote it:

Michelangelo

Michelangelo Machiavelli

Machiavelli Magnifico

Magnifico